Trinidad and Tobago

|

|

Contact person for provided information:

Dr Charisse Griffith-Charles

Senior Lecturer

Department of Geomatics Engineering and Land Management

The University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago

Charisse.Griffith-Charles-at-sta.uwi.edu

Part 1: Country Report

A. Country Context

A.1 Geographical Context

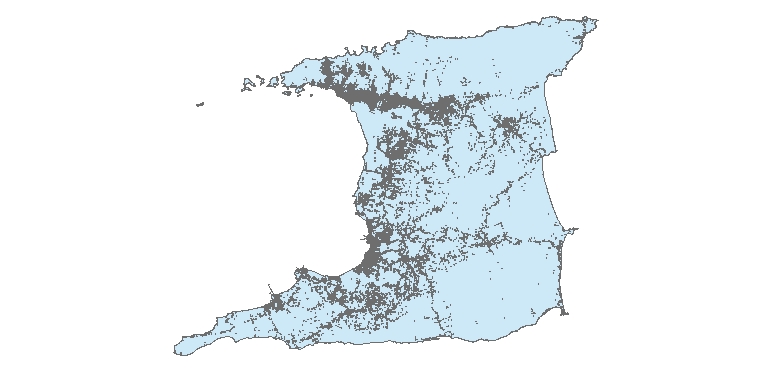

Geographically, Trinidad and Tobago are the southernmost of the Caribbean islands. The country is geologically distinct from the rest of the Caribbean islands, since it lies on the continental shelf of South America in very close proximity to Venezuela. Physically, the state of Trinidad and Tobago is comprised of two main islands; Trinidad, which is 4828 km2 in area and Tobago, which is 300km2. Economically, the island has fluctuated between recessions and prosperity; a reflection of the country’s dependence on its petrochemical industry. The per capita GDP stood at US$16,000 at 2017 (Central Bank of Trinidad and Tobago 2018) for a population of 1.3 million (2011 census). The country is an archipelagic state with a water to land ratio of the 23 islands that comprise the archipelago and the water that is enclosed by the archipelagic straight baselines of approximately 1.4 to 1. The archipelagic water area is therefore 7,158 sq. kilometres and the land area is 5,117 sq. kilometres. The population is concentrated in the urban settlements of the western strip and what is called the east west corridor of Trinidad, and in the southwestern section of Tobago. The rural areas are concentrated in the east of both islands. A mountain range called the Northern Range runs east to west along the north of Trinidad, a central range of hills is located in the centre of the island and a Southern Range runs along the south of the island. In Tobago the highest area is the central Main Ridge. Estimates indicate 20% of the country is used for agriculture in pockets interspersed amongst the more populated western strip of the west of Trinidad and the west of Tobago. The Northern, Central and Southern Ranges of Trinidad, the Main Ridge in Tobago, the Caroni and Naparima Plains, and the Aripo Savannah comprise of large areas of protected forest reserves. The largest wetlands – the Caroni Swamp, the Nariva Swamp and the Buccoo Reef/Bon Accord Lagoon are internationally protected wetlands (under the RAMSAR convention).

Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean context

A.2 Historical Context

The history of the country was shaped by conquest or cession and settlement by the Spanish, French, Dutch, and English, by injection of the multi-ethnic culture of Africans, East Indians, Chinese and Syrian-Lebanese and by fluctuating economic fortunes. Trinidad was a Spanish colony for three centuries before being taken over by the British in 1797. Tobago, however, was not colonised by Spain. Tobago was colonised by France, Holland and in 1803, by Britain. Politically, the two islands have been unified as one country since 1889, independent since 1962, a republic since 1976 and maintain one democratically elected government. The Africans were brought to Trinidad as slaves to work on the sugar plantations. After the emancipation of the slaves, the East Indians were brought in as indentured labourers to work on the sugar plantations. Some indentured labourers were given land in lieu of their passage back to India at the end of the indentureship. Others chose to remain and settled in the rural areas. The emancipated slaves were discouraged from owning land by the Crown setting land prices and parcel sizes out of their reach. Many moved to peri urban areas where they squatted for access to jobs and now comprise large pockets of urban poor. The land law, as in most of the countries of the English-speaking Caribbean, was derived from English common law.

Trinidad and Tobago

A.3 Current Political and Administrative Structures

Trinidad and Tobago inherited the Westminster model of government including the parliamentary democracy traditions of Britain. General elections are held at least every 5 years; the democratic transfer of power is peaceful and usually routine except for a short lived political coup attempt in 1990. Legislative power lies with the House of Representatives with 41 elected members from 41 constituencies, and the Senate with 31 members appointed by the President 16 on the advice of the Prime Minister, 6 by the Leader of the Opposition and 9 independently. Executive power lies with the Prime Minister and his/her Cabinet which is appointed from Members of Parliament. Tobago has its own elected House of Assembly responsible for the administration of the island. The President of Trinidad and Tobago is elected for a 5-year renewable term by an Electoral College consisting of members of the House of Representatives and the Senate. There are 14 municipal corporations in Trinidad including one city and 3 boroughs. The Tobago House of Assembly is responsible for all services provided in Tobago.

Regional Corporations of Trinidad and Tobago

A.4 Historical Outline of Cadastral System

Towards the end of Spanish rule, a numerical system of parcel demarcation was beginning. Large land tracts were marked off, usually with straight north-south and east-west lines in the field and on paper in order to be granted to petitioners. This continued under British rule for Crown grants of land. Parcels were not and are still not coordinated on a national framework but are relatively referenced to the surrounding parcels. On the ground they were initially demarcated at corners with a special type of bottle, with rayo plants, which are a hardy red leaved plant that can be highly visible in the typically dense tropical foliage, and then with iron pegs. Azimuths were measured initially in relation to magnetic meridians, then a local Cassini based grid and then from the 1980s, a UTM grid on the Naparima datum. Solar observations were and still are used for orientation of the lines even though GNSS equipment is sometimes also used for this purpose. A large majority of the early privately transferred parcels were, however, only described verbally in a deed with reference to adjoiners. When populations are small, verbal descriptions, once replicated precisely and exactly in each subsequent deed is sufficient for unambiguous description for the purpose of transaction. Redefinitions, however are not so easy using this method of description. In 1895 the Torrens system was adopted for state grants but private land and lands not alienated from the Crown continued in the deed system. Registration under the Torrens system remained voluntary so only a small minority of owners opted to convert and only if title was insecure. Sketches of parcels in topological relationship were maintained per administrative unit and these were eventually put together to form the cadastral index. Cadastral plans submitted to the Lands and Surveys Department were bound into books, 250 plans to a book, and it was to these that the index showed reference. Trigonometric surveys were first initiated in 1903 and these control points together with a comprehensive aerial survey in the 1960s helped to improve the accuracy of the cadastral index. The current index was digitised in the 2000s and updated in 2014 from new aerial photography but continues to be incomplete. Thousands of plans exist that cannot be placed on the index since they are not coordinated and would therefore require the surveyor to locate them on the index.

Building density in Trinidad and Trinidad

B. Institutional Framework

B.1 Government Organizations

The Surveys and Mapping Division is responsible for maintaining the cadastral index and the cadastral survey plan records for the country in a central repository. The Director of Surveys heads the Surveys and Mapping Division and is responsible for checking and approving the plans held on Torrens system, which is a minority of the parcels. This Division is currently in the Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Fisheries.

The Registrar General’s Department is responsible for registering land deeds presented for registration within the country as well as Certificates of Title for lands held under the Torrens System. This Department is currently in the Ministry of Legal Affairs.

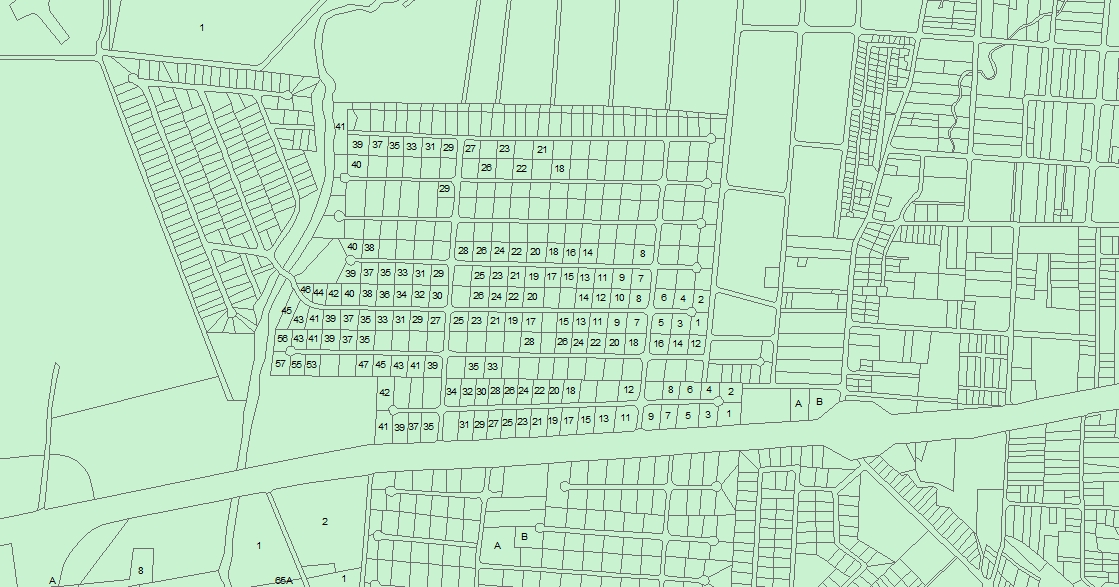

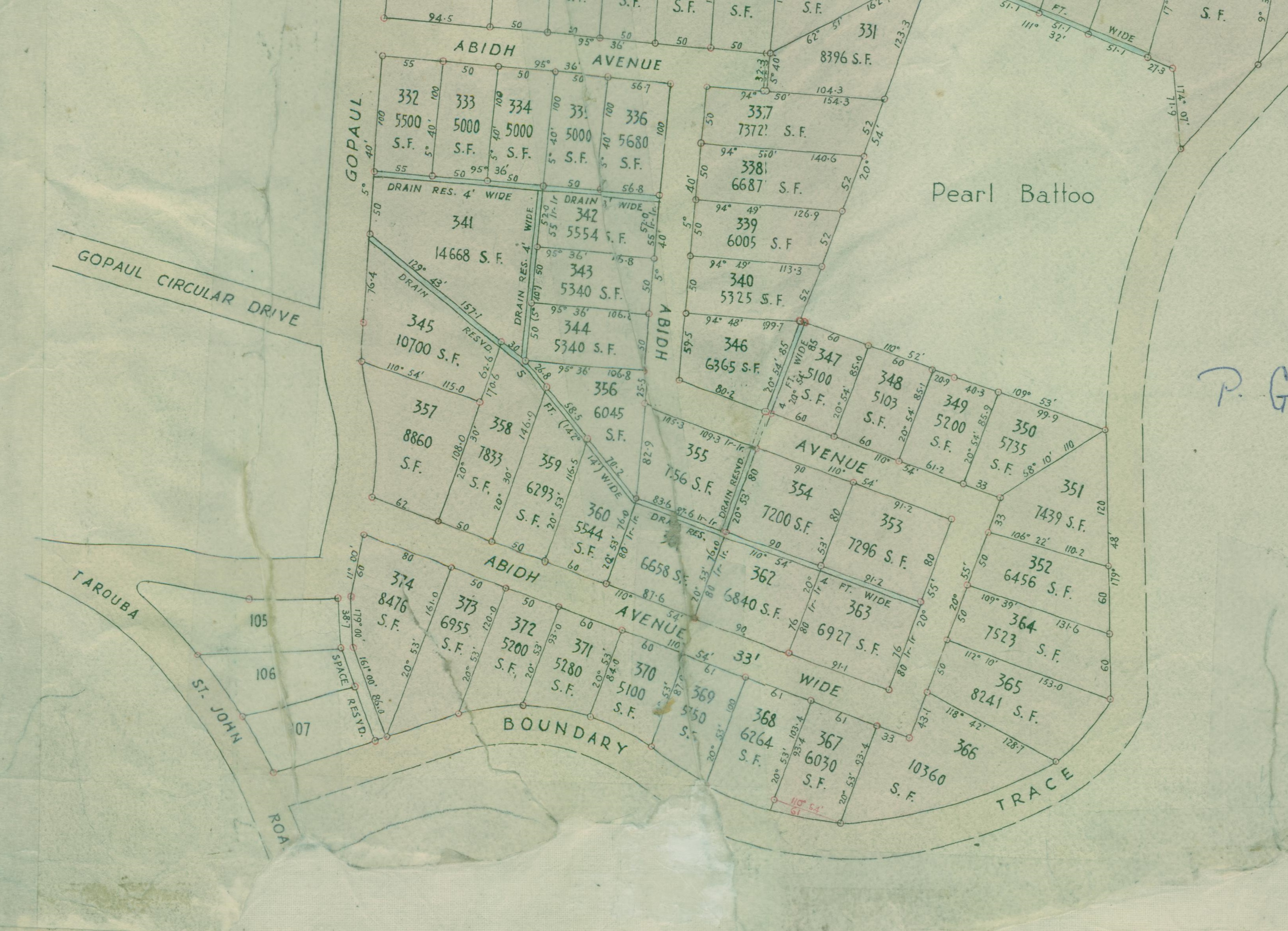

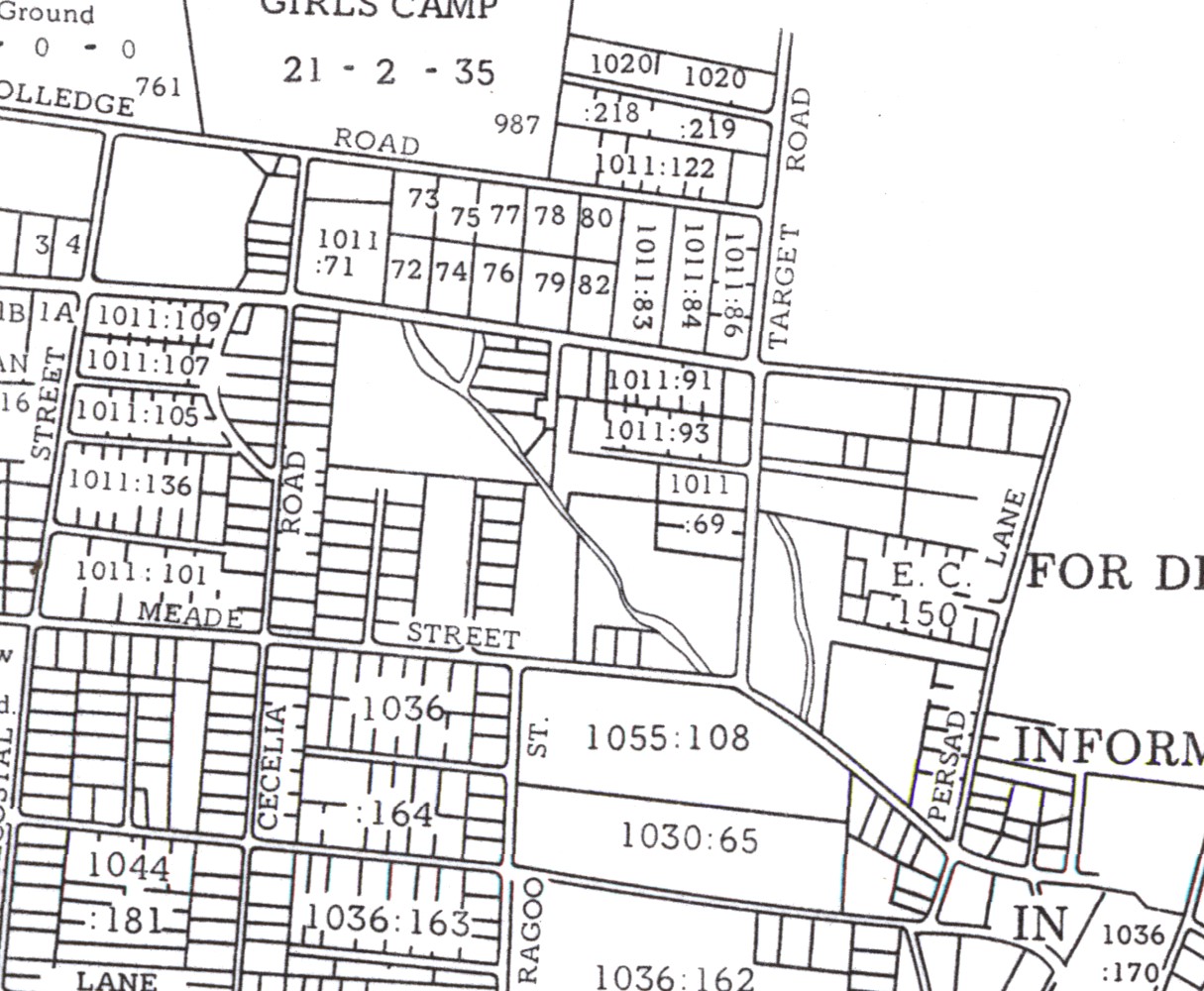

Excerpt of the digital cadastral index

B.2 Private Sector Involvement

Private land surveyors conduct cadastral surveys on private lands but can also obtain a Survey Order, which is a public sector request to perform surveys on state lands. The state does not have the surveying capacity to perform all the surveys required by the state for leases, and compulsory land acquisition.

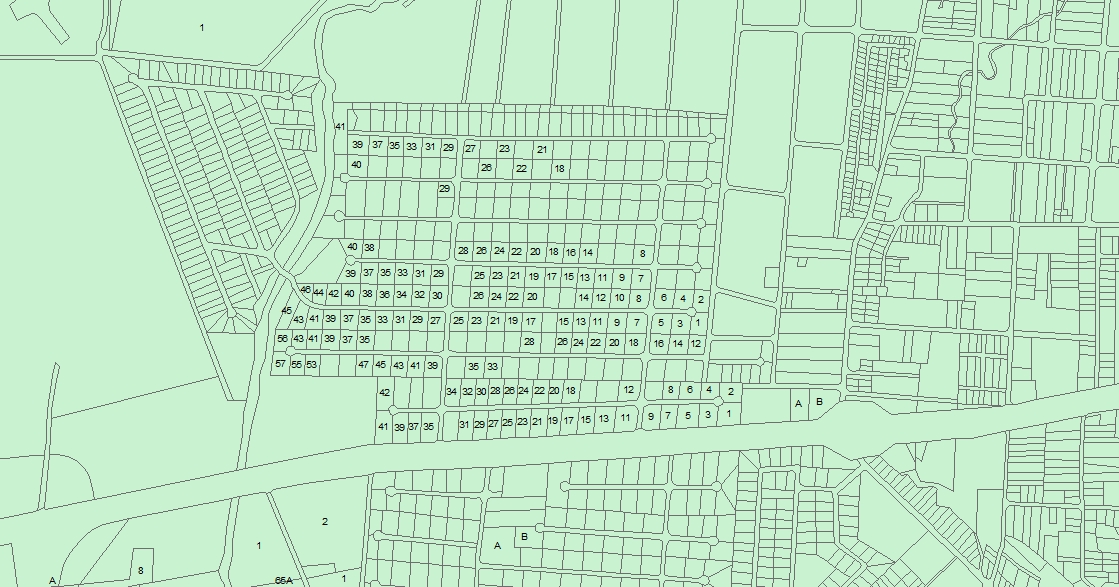

Detail of cadastral plan

B.3 Professional Organization or Association

The Institute of Surveyors of Trinidad and Tobago (ISTT) (http://www.instituteofsurveyors.com ) is the professional organisation for land surveyors, quantity surveyors and valuation surveyors. The membership numbers about 200 of which the majority are land surveyors, not all of whom are cadastral surveyors. The ISTT is a member of FIG.

The website of the Institute of Surveyors of Trinidad and Tobago (ISTT)

B.4 Licensing

Licensing of cadastral surveyors is managed by the Land Survey Board of Trinidad and Tobago (LSBTT) which is a state funded board. An applicant for licensing requires a first degree in a land surveying programme. The applicant can then embark on a two year apprenticeship evidenced by approved reports under an experienced and licensed land surveyor prior to undertaking a practical trial survey examination and a viva voce or oral examination conducted by the LSBTT. Success in all three assessments will lead to a grant of a licence.

The Land Surveyors Act provides for licensing

B.5 Education

There is one university programme that offers a BSc. degree in land surveying (now called Geomatics). The programme is delivered at the Department of Geomatics Engineering and Land Management in the Faculty of Engineering at the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine. This is a regional university and therefore is attended by students from all the countries of the English-speaking Caribbean. The graduating output of the land surveying programme started out in 1986 at 7 and grew to a high of about 50 in 2008 and is now being managed to reduce to a figure that is more in keeping with the needs of the country and the region and the capacity of the Department. The graduating output in 2015 was 21. Not all of the graduates from this degree remain in the country or continue into the profession of land surveying. Some graduates go into GIS management, land administration, estate management, or other completely different professions. Not all of the ones that continue in land surveying decide to become licensed to perform cadastral surveys and may instead focus on engineering surveying. The Department of Geomatics Engineering and Land Management is an academic member of FIG

Department of Geomatics Engineering and Land Management

C. Cadastral System

C.1 Purpose of Cadastral System

The cadastral system has a legal (juridical) purpose and is comprised of a cadastral mapping and a separate ownership registry. Most of the formally registered land is held under a rudimentary deeds recordation system with the concomitant problems of restricted and time consuming access to tenure data. A parallel Torrens type title registration system has existed since 1895 but, since the conversion process prescribed in the legislation is voluntary and sporadic, and the regulatory and institutional mechanisms for conversion is lengthy and costly, it has never held more than a small minority of the land parcels. There is no fiscal cadastre. Land taxes are paid on the individual parcel based on an individual assessment of the property. At the moment land taxes have been suspended for revision of the process and are due to be reinstated. Planning authorities use the paper cadastral index for noting applications for use and development.

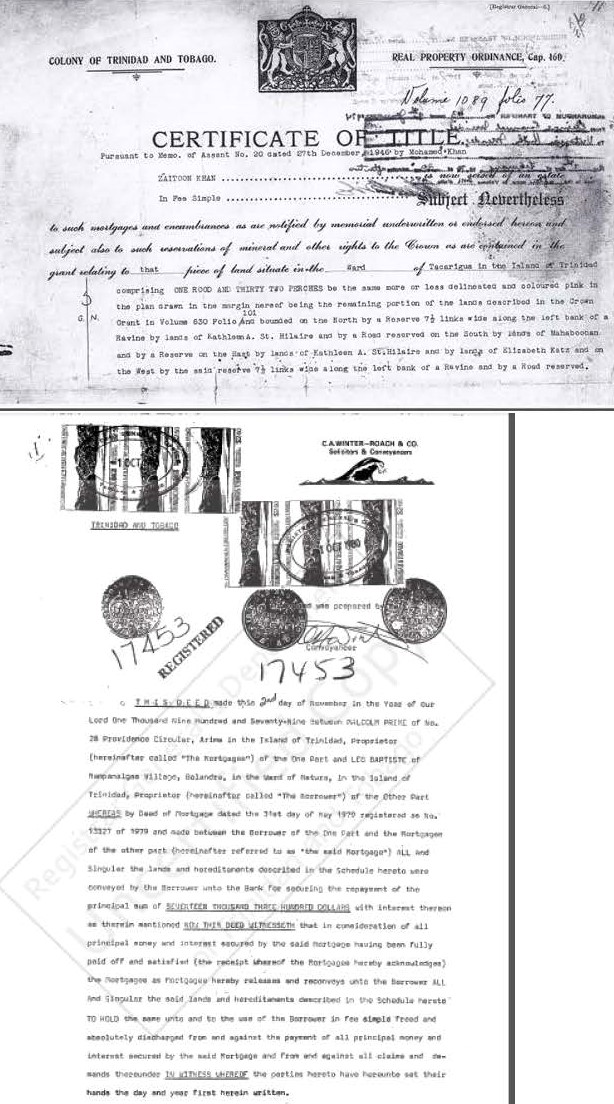

Certificate of Title and deed documents

C.2 Types of Cadastral System

There is one comprehensive and centralised cadastral system covering the entire country. The many informal and illegal settlements of long standing are not reflected in this cadastre. Some estimates are that some 50 thousand informal parcels exist on state lands and these do not appear in the formal cadastre. Informal occupation on private land also do not appear. Many parcels have never been surveyed but are described verbally in a deed. These do not appear in the cadastral index. Some survey plans have not been submitted to the repository and so do not appear in the cadastral index. There are therefore many gaps in the cadastral index and in the legal land registry. The framework for a subset cadastre for state lands has been developed but not completely populated with the attribute information required for use. The purpose is for management of state leases. The parcels in this subset are already part of the national cadastre.

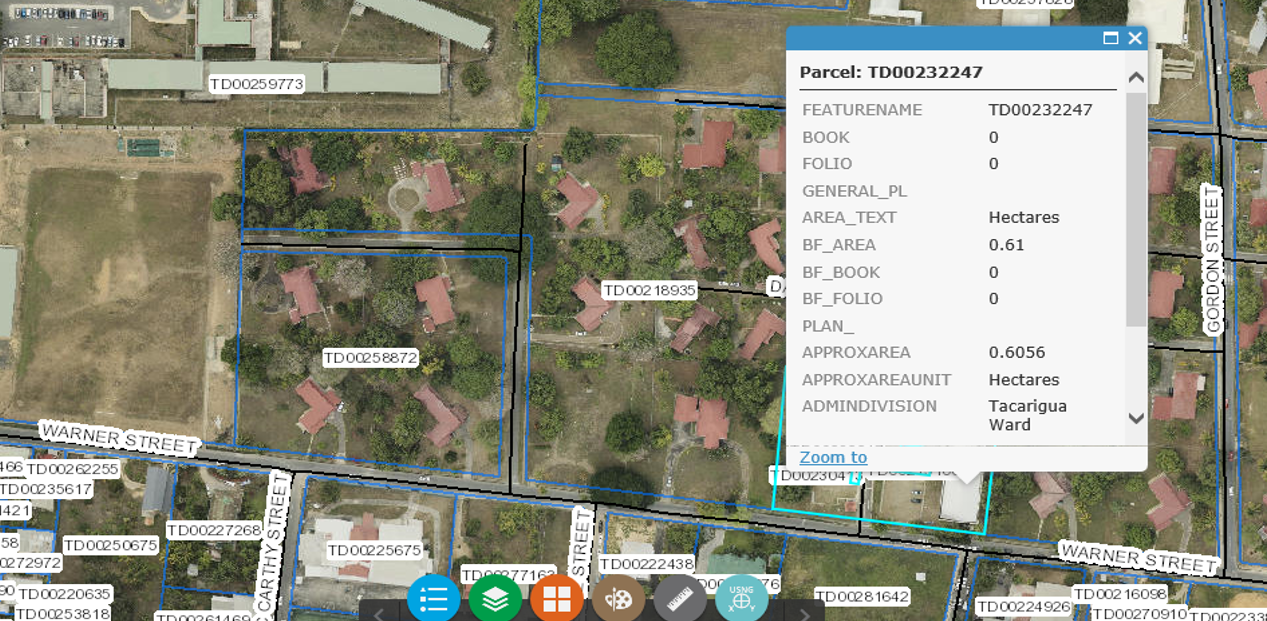

Formally surveyed parcels only are captured on the cadastre

C.3 Cadastral Concept

The individually owned parcel is registered by the surveyor at the centralised state repository for the country. These parcels are 2D parcels. 3D parcels are indicated by vertical cross sections drawn on a 2D plan. All parcels are therefore referred to the surface parcel. Individual parcels are registered but parcels adjoining each other can be amalgamated but only if all the required applications are approved and the adjoining parcels become one parcel. Condominium units are registered only as a subdivision of the parent parcel belonging to the condominium company.

C.4 Content of Cadastral System

The cadastral index map is comprised of separate sectional sheets and these are kept at the Lands and Surveys Division. The index presents the parcels in context and indicates references to the books or plans where the cadastral survey plans are kept. These cadastral survey plans give information on the dimensions of the parcel. The index is digital and the plans have been scanned. There is no unique parcel reference number so knowledge of the location of the parcel is needed to access the index and then the book or plan where the boundary information is graphically presented. There is usually no link to the deed related to the parcel noted on the plan. If the parcel is held under the title system the certificate of title number is noted on the plan and provides a link to access the title information in the Registrar General’s Department.

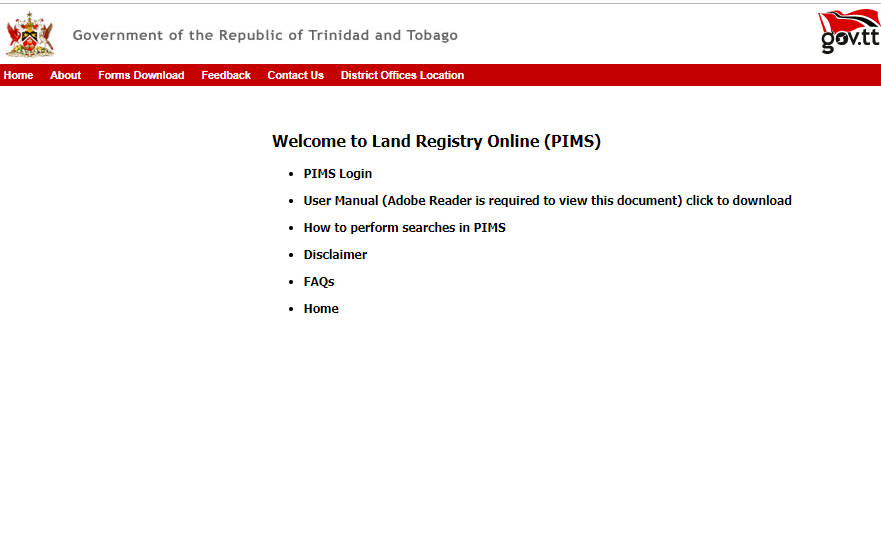

The deeds and title information is kept at the Registrar General’s Department. The deeds are sequentially housed in bound volumes so that the individual deeds must be accessed with knowledge of the number and year of registration of the deed and transaction or by referring to the index of transactions with knowledge of vendor and purchaser. The titles are also held sequentially in bound volumes in Torrens fashion so there is no general map as in the English version of title registration but the individual parcel is inscribed on the certificate of title. The deeds have been scanned and indexed back to 1970 but the Certificates of Title have not yet been scanned.

Paper Cadastral Index

D. Cadastral Mapping

D.1 Cadastral Map

The cadastral map is a physical map that has also been digitised from the comprehensive 1:10,000 scale index, with incomplete attribute information on the location of the referenced plan. The graphic layer contains parcel polygons and the attributes noted are the parcel owner at time of survey, the area of the parcel, the plan reference to the survey plan, and the land cover type in a few basic categories of road, water body and parcel.

Excerpt of digital cadastral data

D.2 Example of a Cadastral Map

D.3 Role of Cadastral Layer in SDI

The cadastral index is uncoordinated and cannot be integrated with other datasets at scales larger than 1:10,000 although there are urban and suburban areas that are more precise. An NSDI council has been recently set up to establish the structure of an NSDI for the country. The water utility, the valuation division, and the planning agency use the index for general planning functions.

E. Reform Issues

E.1 Cadastral Issues

Accessibility: The lack of a unique parcel reference number means searches for information for both professionals such as land surveyors and attorneys, and members of the public is a lengthy and tedious task.

Need for systematic registration: The large percentage of informal parcels and formal but unsurveyed parcels indicate a need for systematic registration. This option is, however, too expensive for the country at the moment.

Currency: Survey plans are not coordinated so there are now thousands of plans received by the Lands and Surveys Division that cannot be located on the cadastral index and therefore cannot be placed in proper location.

Land Registry website provides access to deeds for a fee

E.2 Current Initiatives

A current project is underway to georeference a small subset of the existing index more closely to the ground by fitting individual plans to the comprehensive captured orthophotography of 2015. This will not be helpful to most users until a comprehensive set of parcels are put in but is a start.LiDAR scanning was also done and a DTM created to provide better elevation data.

Land surveyors have been asked to provide at least one GPS provided coordinate on the survey plan so that the plan can be easily inserted into the index. This may not address the backlog of plans but will reduce the incidence of the problem occurring in future.

F. References

Griffith-Charles, C. and E. Edwards. 2014. Proposal for Taking the Current Cadastre to a 3D, LADM Based Cadastre in Trinidad and Tobago. 4th International FIG 3D Cadastre Workshop. 9-11 November 2014, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. ISBN 978-87-92853-28-8 (printed). ISBN 978-87-92853-29-5 (online).

Griffith-Charles, C. and M. Sutherland. 2013. Analysing the Costs and Benefits of 3D Cadastres with Reference to Trinidad and Tobago. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems. Vol. 40: July 2013. 24-33.

Griffith-Charles, C. 2011. The Application of the Social Tenure Domain Model (STDM) to Family Land in Trinidad and Tobago. Land Use Policy. Vol. 28:3. 514-522. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.10.004

Done, P. and M. M. Robertson. 1988. The Cadastral System in Trinidad. Survey Review, 29, 228

Griffith-Charles, C. and J. Opadeyi. 2009. Anticipating the Impacts of Land Registration Programmes. Survey Review. Vol. 41:314. 10 pages.

Griffith-Charles, C., 2004. ‘Trinidad: ‘We Are Not Squatters, We Are Settlers’’ in R. Home and H. Lim (eds) Demystifying the Mystery of Capital: Land Tenure and Poverty in Africa and the Caribbean. London: Glasshouse Press. 99-120.

Stanfield, D., Singer, N., 1993. Land tenure and the management of land resources in Trinidad and Tobago. Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI.

Part 2: Cadastral Principles and Statistics

1. Cadastral Principles

1.1 Type of registration system |

|

title registration

deeds registration |

1.2 Legal requirement for registration of land ownership |

|

compulsory

optional |

1.4 Approach for establishment of cadastral records |

|

systematic

sporadic both, systematic and sporadic all properties already registered |

2. Cadastral Statistics

2.1 Population |

1,300,000 |

2.2a Population distribution: percentage of population living in urban areas |

13 |

2.2b Population distribution: percentage of population living in rural areas |

87 |

2.3 Number of land parcels |

500,000 |

--- Number of land parcels per 1 million population |

384,600 |

2.4 Number of registered strata titles/condominium units |

0 |

--- Number of strata titles/condominium units per 1 million population |

0 |

2.5 Legal status of land parcels in URBAN areas: |

|

percentage of parcels that are properly registered and surveyed |

50 |

percentage of parcels that are legally occupied, but not registered or surveyed |

20 |

percentage of parcels that are informally occupied without legal title |

30 |

2.6 Legal status of land parcels in RURAL areas: |

|

percentage of parcels that are properly registered and surveyed |

20 |

percentage of parcels that are legally occupied, but not registered or surveyed |

30 |

percentage of parcels that are informally occupied without legal title |

50 |

2.7 Number of active professional land surveyors |

100 |

2.8 Proportion of time that active professional land surveyors commit for cadastral matters (%) |

90 |

--- Approx. full-time equivalent of land surveyors committed to cadastral matters |

90 |

2.9 Number of active lawyers/solicitors |

100 |

2.10 Proportion of time that active lawyers/solicitors commit for cadastral matters (%) |

90 |

--- Approx. full-time equivalent of active lawyers/solicitors committed to cadastral matters |

90 |